Helix Lo

Graduate Student, Department of Advanced Social and International Studies

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo

Abstract

Hope is essential for one to live, and for one to imagine the future. It will not be a surprise for someone to highlight the necessity of a continuous search for hope in one’s life. Similar expectations are applied to governments and international order, too. The promotions of rule of law, freedom, plurality, tolerance, and human rights are all visible attempts to encourage state parties and individuals to endeavor for attaining the hope of a peaceful future that is grounded on liberty and equality. Fear, in contrast, is regarded as a taboo and should not be expressly mentioned. This article holds a contrary position to the proponents of building a ‘hopeful’ society, arguing that hope and fear are in a relative position and neither of them should be abandoned or stigmatized. Without hope, fear cannot be felt; without fear, hope cannot be perceived. This article stays close to this state and suggests that fear is the core unit of the contemporary international order and theorizes how fear can be manipulated to control hope. Whether the order can be sustained or not depends on the degree of how unified and universal fear is. If fear diversifies, hope cannot be sustained and hence will lead to a situation where everyone is in pursuit of their interests. Hence, if an order needs to be sustained, fear but not hope should be the foremost important emotion that civil society, scholars, and politicians be aware of. Otherwise, the order will never be direct to a peaceful ending of human society.

Keywords: Politics of Emotion, Fear, International Order, Human Society, Manipulation

1. Introduction

On 24 January 2023, Doomsday Clock was moved ten seconds forward, having 90 seconds left before the world ends (Science and Security Board, 2023). The Clock, certainly, is not a calculation done by the earth itself. Instead, it is an artificial ‘clock’ established by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1947, indicating how close we are to doomsday. Over these 70 years, the Clock never goes anti-clockwise and has moved forward for 300 seconds already. The decision to move to 90 seconds, as explained by the Board, is mainly because of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which was intensified in 2022, and the nuclear threats that come alongside it. The War not only reaffirms the weight of power (e.g. nuclear weapons, veto power in the security council, and energy resources) in the international society, but also evokes further concerns about how the existing liberal international order could be further undermined by superpowers, if not only autocracies and authoritarian countries, and regional warfare (e.g. the latent military conflict between China and Taiwan in Southeast Asia).

Indeed, worrying signs of ‘liberal order in danger’ has been continuously found in the contemporary world. On the one hand, for example, democracies are facing a decline in recent years. Summarized by Bastian Herre (2022), the data of Varieties of Democracy[1] implies that there is an all-rounded decline in terms of the number of democracies, of citizens living in democracies, and of democratic rights which citizens enjoy. In stark contrast, there is an increasing number of autocratic countries with more people living there. Albeit the decline could be reasonable as either the consequence of the previous or the starting point of, another wave of democracy[2], on the other hand, visible challenges are found among states in recent years. Equating the liberal order as a rule-based order, three major challenges are suggested (Chatham House, 2015a): Legitimacy, Economic Declines, and Self-Confidence. Whereas the second concerns the stability of the order when the economy is declining and/or underdeveloped and the third questions the naturality of the order, the first is most critical nowadays – the increasing advocates of the ‘might is right’ approach (p. 1). China is a leading example of this type of challenge. Notoriously agreed with the violations of China confirmed on various human rights aspects (e.g. Amnesty International, n.d.; Burnay & Pils, 2021, p. 249; OHCHR, 2022), the attempts which the Chinese government devoted to altering the norms and values of human rights and to stress the primary role of state sovereignty have also been commonly found (e.g. Burnay, 2021; Foot, 2020; Hsu & Chen, 2020; Richardson, 2020). For example, at the meeting of China-Germany-European Union Leaders held on 14 September 2020, President Xi Jing Ping stressed publicly that, there is ‘no one-size-fits-all path for human rights development in the world. There is no best way, only the better one (The State Council, 2020).’ The ‘might is right’ approach has undoubtedly empowered states like China to be capable of defending themselves from the criticisms of violations of the rules established in the so-called ‘universal’ liberal order. Witnessing the inabilities of the international order and its institutions from helping citizens who suffer from state abuses, halting the continuous and aggravating violations of rules that states behave, and terminating warfare initiated by powerful states, it is not surprising to be asked, if not anger prevails and hope still exists, that ‘where and how should the current international order and society go?’

In The geopolitics of emotion: How cultures of fear, humiliation, and hope are reshaping the world, Dominique Moisi (2010) expressed his thoughts on the role of emotion – mainly Hope, Humiliation, and Fear – in the international society and explained how countries are (were) associated with these emotions. In Chapter 2, he focuses on the emotion of hope and suggests that the source of the transition of the Asia continent to hope is their material prosperity. Whereas China and India are two leading countries in representing the hope of reclaiming their status and promoting themselves further in the international arena respectively, yet, Japan is facing anxiety about its future. The next chapter shifts to the relationship between the West and Islamic and argues that humiliation found there involves elements like historical roots (e.g. the declining influence and power of the Arab-Islamic world), religious exclusiveness (e.g. Islam and Christianity), and the utilization of the emotion as diplomatic tools (e.g. exploitation of guilt). The theme of fear follows in Chapter 4, where the lens remains on the West. The fear in the West contains multifaceted factors, including the loss of jobs caused by economic declines, the fear of others especially Muslims and terrorists, and the decline of democracy by which their moral ground is being negatively affected. Although all these countries mentioned do not experience merely one emotion at a time, Moisi particularly depicted some countries where all three emotions are observed. Russia, for example, suffers from the humiliation – of losing international status – imposed by the end of the cold war, and has a xenophobia tradition as the course of fear. Yet, hope emerges from its economic and material growth, nationalism, and sense of pride.

Overall, Moisi portrayed the three emotions observed from different countries, where hope is presented in a way that is more contributive and positive than fear and humiliation. He also suggested that the international society should seek a way to attain more hope with less fear and humiliation, for which learning the emotion of other cultures is essential for achieving a more peaceful and tolerant society. While Hope functions as motivation, resilience, and a chance of change for a human to live (Olsman, 2020) and optimism is necessary for facing a complex and tumultuous world (Chatham House, 2015b), however, this article disagrees with the overemphasis placed on hope and the attempts to derogate and neglect the function and role of fear for the construction of a better future for human beings and the international society. It argues that, first, the liberal rule-based international order is maintained by fear but not hope. Second, hope cannot be recognized if fear does not exist, and vice versa. Third, by manipulated fear, hope can be anticipated and articulated to designated positions. It, therefore, returns to realism and stays aligned with philosophers such as Rene Descartes, Tomas Hobbes, David Hume, and Baruch de Spinoza who had either stressed the presence of fear in pair of hope or the function of fear as the foundation of the society.

Instead of hope, this article hence suggests that fear is the core mechanism of the contemporary order and should be the main emotion that we should focus on if we would like to understand the problems of and sustain the order for a peaceful society. This article aims to answer three major questions: How could the concepts of ‘hope and fear come as a pair’ and ‘fear as one of the most fundamental sources of hope’ further our understanding of state behaviour and the international order in the contemporary world? How hope can be articulated by fear? Why should we be cautious of artificial fear? This article offers an extensive exploration of the function of fear to states and the international society. It holds that the liberal order is in fact maintained by fear and if fear diversified, hope follows, and conflicts occur. It further suggests that, to achieve peace and preserve the liberal rule-based order, politicians, scholars, and civil society should pay their very attention to any artificial creation of fear and its utilization for specific unilateral political gains. They should also try to search for ways to further the sharing of a common fear across countries. Otherwise, conflicts would never cease.

The next section begins with a brief theoretical explanation of the emotion of hope and fear, follows with the explanation of the relationship between fear, human society, and the contemporary liberal international order. The fourth section proposes a calculation of hope and fear and suggest that excessive usage of artificial fear should be avoided to sustain the order and peace. Before entering the concluding discussion, two imaginations of the future of the international order are provided as to predict the development of the human society after 20-25 years.

2. Hope and Fear

In ancient Greek, as summarized by Gravlee (2020), hope is regarded as unreliable, unpredictable, empty, and allure (p. 5), and is a host of phenomena which includes complex elements such as despair, pain, and memory (p. 13). Different philosophers have been associating hope with different elements. For example, Plato connects hope with dreams and imagination, whereas Aristotle argues that hope is about confidence and trust, and deliberation is the stage after imagination (p. 19 – 21). Hope has also been labelled as a motivational tool. For example, desperate hope helps infuse agents with valour to act courageously (p. 10). It is therefore hope should not be simply regarded as a prediction but as are attitudes for motivation (Vogt, 2017, p. 45). Some philosophers, moreover, link hope with memory and suggest that memory provides a foundation for imagination, and hence, hope (e.g. Gallagher et al., 2002; Frede, 1985; Snyder, 2000); some argue that hope is about trust and confidence (e.g. Lopez et al., 2018; Post, 2009; and also Aristotle); some said it is about value (e.g. Moffitt et al., 2011; Vohs & Baumeister, 2016). Whereas the associations they purposed may not be exclusive to each other, it seems there is not a consensus on what contributes hope the most.

If the aforementioned are about the factors that contribute the hope, the following is about the opposite of hope in terms of emotions. Some philosophers, interestingly, connect hope with fear. For example, in The passions of the soul and other late philosophical writings, Rene Descartes (2015) describes hope and fear as two dispositions of the soul (p. 264). The former persuades the soul to desire and the possibility of achieving it, whereas the latter persuades the soul that it will not be achieved. (p. 264). He believes that hope and fear can be held by a person at the same time and if either of them is entirely absent, hope becomes confidence or fear becomes despair (p. 264). Baruch de Spinoza somewhat shares the same thought with Descartes. In Ethics (1996), he wrote that ‘there is no hope without fear, and no fear without hope (p. 95).’ A similar ground was proposed by Aristotle too, that hope is a necessary condition for one to fear (Rhetoric, 1383a7). Thomas Hobbes is another prominent philosopher who discussed fear and hope. From his work Leviathan, it is evident that fear shares a significant position in his philosophy. He believes that the nature of the state is a war against everyone which will result in continuous fear of them. Yet, he also expressed his views on hope. In Elements (1969), Hobbes connects hope and fear with expectation. Whereas hope is an expectation of the advent of something good, fear is the expectation of evil (9.8), and such variation depends on the causes (9.8). To these philosophers, hope and fear are two sides of a coin. Depending on the information we received, the context we are in, and the imagination we can project, hope and fear can be felt differently. Once hope or fear is perceived, another should not be absent in one’s emotion.

Although philosophers have different interpretations of what fear and hope are and how, if they are, they are interrelated, one common proposition that they share is the uncertainty of the future. It is the uncertainty of good and evil that gives rise to fear or hope (Hume, 2000, p. 81); it is the uncertainty of the future that induces doubts (Spinoza, 1996, p. 81); it is the uncertainty that stimulates possibility and imagination (Bloch et al, 1986; Descartes, 2015; Post, 2009). To summarize the relationship between uncertainty, possibility, imagination, and hope and fear, it is from uncertainty, we found possibilities; from possibilities, we start imagination; from imagination, we saw hope and fear. All three components which lead to the emergence of hope and fear can only appear in a world where the future is not closed, which is similar to the viewpoints of some scholars (e.g. Bloch et al, 1986; Gravlee, 2020).

3. Human Society, Universal Values, and International Reality

The definition and perception of emotion vary in human society. If two persons are asked ‘What is happiness?’, the person who just finished his/her work and left the office would probably say ‘For now, I am happy because I can finally return to my home and take a rest’; the other person who just married his/her love would probably say ‘I am glad that I finally settled with my partner’. Although both answers somewhat connect with the emotion of joy, the perception, cause, and reasoning of happiness are highly dependent on one’s background and capabilities such as experiences, imagination, culture, and/or age, which has been well studied. For example, a study conducted by Yukiko Uchida and Shinobu Kitayama (2009) found that the happiness of the Japanese was having a stronger relationship with social harmony, whereas it was the hedonic experience with personal achievements for Americans. Another study reveals that one source of happiness for younger people is excitement, and it turns into peacefulness when they become older (Cassie et al., 2011). Emotions of human beings, therefore, never have an immutably static, unified, and universal definition.

Hope and fear are also subject to this variation. Imagine two persons living in a city, named S and T. S is a person who does not have his/her place to live and suffering from starvation, whereas T is a person who has affluent monetary and material resources to live on. In this situation, will S and T share the same set of hope and fear? Certainly not. The fear of S is about whether he/she can be alive tomorrow and thus hopes for food to live on. T, instead, fears losing his/her status, and hopes for the continuity of the living standard that he/she is now having. When S becomes able to secure enough food and supports for his/her living in the city, the fear of not being able to live soon turns into the fear of returning to the previous situation, and hence hope for maintaining or improving the newly achieved living standards. When T experienced a drop in his/her assets in the future, he/she will therefore fear further reduction and hope for retrieving what he/she had in the past. The example is oversimplified, indeed, in that it does not include miscellaneous factors such as the contextual environment of the city, the education they received, and the values they uphold. Yet, it is clear enough to assert the possible variances between two or more parties of what hope and fear truly imply to them in different contexts.

While variation naturally exists, it is not detrimental until individuals decided to pursue their interpretation of hope unlimitedly and when the objects of hope that they seek somewhat overlap with the others. Hobbes expressed his thoughts on this matter in Chapter XIII of Leviathan (1914), believes that the equality of men in terms of their abilities will bring them to the ‘equality of hope (p. 63)’, in which the two men who intend to attain the same whilst exclusive thing will ultimately become enemies. The consequences of the arbitrary pursuit of what an individual can imagine echoing with the notion of the state of nature as proposed by Hobbes, by which everyone turns against everyone (p. 67). The creation and promotion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for example, can be therefore perceived as an international attempt to establish a universal unification of hope across cultures and continents. The Universal Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, which represents a milestone of universal values in human history. It expresses the hope for a human living with, including but not limited to, dignity (e.g. Preamble; Art. 1; Art. 22), freedom to residences, belief, expression, and thoughts (e.g. Art. 13.1; Art. 18; Art. 19), and rooms for personal development (e.g. Art. 29). As these hopes expressed are not exclusive, the equality principle stressed by the Universal Declaration offers a universal certainty [conceivable image] for all mankind, regardless of their place of origin, ethnic background, religious beliefs, and/or material status. It stirs possibilities and imaginaries among individuals of what they can become and how they can be used in practice. Simultaneously, the Universal Declaration performs as a hope for the states, as a possibility that they should strive to attain. For the benefits that human rights values and the document present, it is reasonable to believe that it is a hope for all state parties and individuals to fully achieve it.

Two reflective questions follow, however. First, why is it necessary to have this document of hope, if it can be regarded as hope, issued and signed in black and white? Second, is hope the sole emotion that it presents? Imagine a scenario in a property market. After searching for a while, a person finally finds his/her dream house and decides to purchase it. Now, if there are no additional factors which might lead to the failure of the transaction (e.g. screening process required by the bank or owner of the house), then why should he/she hope for a successful transaction when he/she can purchase it successfully? Hope (and fear) existed with probability and attainability, as Plato and others discussed when the person yet knew whether a dream house could be found. Though, the emotion soon dispersed when it is found. Moreover, if all past transactions were completed smoothly without any troubles between buyers and sellers, to what extent would the significance of black-and-white contracts be recognized? Indeed, even when problems are not foreseen, transaction contacts are signed nowadays because they function as a security guard for involved parties per se. However, if troubles never exist (e.g. the buyer refused to pay after he/she received the products from the sellers) [fear of perceivable troubles/cost], why would one realize there could be troubles and hence recognize the essentialities of contracts in transactions [hope for preventing and resolving troubles/interest]? Therefore, hope and fear are not independent but are relative emotions – the hope for a smooth and productive transaction in this scenario is distinguished and confirmed as hope only when there are referenceable failures in the past which induce parties to deliberate of, and fear, the same consequences.

The model presented above returns to one core component of the emotion of hope and fear, discussed by scholars such as Descartes, Spinoza, Hume, and Bloch, namely uncertainty. On the one hand, human beings are not machines that have their behaviour formulated in a unified and unchangeable way. On the other hand, no one on earth can be assertive of the next moves of others. The facts and information wandering in the memories of a person guide his/her imagination of what could happen in each scenario, in which the process is stimulated by the degree of trust that holds for a self and others. Consequentially, any attempts to establish certainties (e.g. we are free, or we can be free) will inevitably incur uncertainties (e.g. what if we are not free, or what if we cannot be free). The relationship between hope and fear is more appropriate to be conceived of as two sides of a coin, that a person who holds a coin will have no choice but to obtain both sides of it. Without flipping the coin, or being able to do so, however, that person would never know if the side he/she is facing is the front or the back. That side could be the front or the back, or neither, in that the person does not know what differentiates the ‘front’ from the ‘back’, and what it means by the ‘front’ and the ‘back’ if that side is the only side in his/her knowledge. Whereas the model suggested here is somewhat familiar with the theory of Schrodinger’s Cat, the emotion of hope and fear share the same properties with the coin unexceptionally in human society.

The Universal Declaration and relevant documents which promote the values of human rights are subject to the above argument too. If human beings have never been deprived of the liberty to think, believe, express, and live, why should they be worried? If human beings have never failed to recognize and exercise all these rights with respect and tolerance for others, why should they be reminded of doing so? If human beings have never lived without equality and dignity, why should the documents be concerned about it? If all human rights have never been violated by every single individual, society, and state party since their first ever existence before, why should the documents be formalized and signed with enforcement detail? Through these questions, it is now clear that hope is not the sole emotion contained in the Universal Declaration or other relevant documents, nor is this universal hope the sole thing they promote. Whether it is intentionally or unintentionally, consciously or unconsciously, an universal sense of fear is circulated simultaneously with hope when the coin ‘Human Rights’ was given to people. That is, the fear of being disenfranchised from the right and liberty to live, beliefs, cogitation, and expression motivates individuals and civil society to pressure hard on state parties and to resist when repression is perceived. Ideally, this fear will impel individuals to be respectful of the rights and freedom of others and not to infringe on them, and states will be consistently reminded of the potential violation and move forward to better promotion of them.

Having the relativism which connects hope with fear in the promotion of universal values clarified, moreover, it is time to shift to the origin(s) of the contemporary international order (and the values that come along with it) with the question of: ‘Is the order a creation of hope?’ The order nowadays promotes multilateralism and a rule-based system that delineates the behavioural standards for state parties and individuals. International platforms are built for state parties and civil society to cooperate and search for resolutions in a civil way when conflicts occur, such as the United Nations Security Council and the International Criminal Court. Conventions such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child not only list the duties of state parties but also seek greater empowerment to individuals for their participation in the political and civil society and to envisage for further personal development. It is the same for the promotion of democratic and liberal values, in which a liberal society is perceived to be more prone to peace and tolerance (e.g. Babst, 1964; Kent, 1915; Mintz & Geva, 1993; Rummel, 1983; for counterarguments, see Daase, 2006; Layne, 2014; Rosato, 2003). These institutions and values that the contemporary international order cherishes and portrays indubitably contain hope, function to reduce potentially destructive conflicts, and build and sustain a peaceful and intellectual society.

However, it is debatable to suggest hope as the origin of these attempts and efforts. As argued previously, hope cannot be recognized without fear. Hence, if the order was created of pure hope, then it should not be created at a time when there is a need for hope. Searching back to human history, the underlying institutions which contribute to the contemporary liberal international order are all established when chaos was experienced. For example, the establishment of the two greatest interstate cooperating institutions – the League of Nations and the United Nations – were born after two historic brutal warfare – World War I and World War II – which had caused tremendous damage with an enormous amount of deaths respectively. Without the history of conflicts, war, death, and chaos, fear of such consequences would not exist. If these sorts of fear do not exist in human and international society, there is no need for common power (see Hobbes, Leviathan, 1914, Ch. XIII-XV; Ch. XVII), nor coercive forces (see Niebuhr, 2013, Ch. I; and also Ch. VIII for further arguments), nor (rule of) law (see Dicey, 1959; Raz, 2009; Summers, 2013), nor social contracts (see Rousseau, 1762/2008). As if every autonomous agent in a society eternally behaves in the good faith of others, there seems to be no room to regulate them to act in good ways with specific power and rules. Therefore, although the establishment of the United Nations, the following covenants and conflict resolution institutions, and the liberal have a strong association with hope – the hope for having a more sustainable and bright future of all mankind, they were given birth in the light of fear – fear of replication of the tumultuous and brutal experiences suffered in the past. In short, the contemporary international order is born from fear, whilst born for hope.

To further the arguments and accentuate the role of fear in the order, one crucial component of the successful maintenance of the liberal international order is the extent of fear that is commonly felt among the members of a society. In the creation of the League of Nations, though it was created with the efforts of President Woodrow Wilson of the United States and especially related to his proverbial Fourteen Points, the United States was never an official member of it. The reasoning behind lengths but one major reason is that the interest in joining the League was not sufficient to convince the congress to alter traditional American foreign policies and to get involved with European politics and internationalism (Office of The Historian, n.d.). Its absence in the League has been regarded as one of the explanations for the failure of the League in sustaining peace (e.g. Eloranta, 2011). Albeit the decision of the United States was about the interests of the state (i.e. cost of joining the League versus the interest of joining it), the inadequate motivation it had can also be interpreted as a result of a lack of fear. The United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, when ships of the States were sunk by German submarines. In its battle, over 50 thousand military service members died in battle and more than 60 thousand died in service (Smith, 2017). Yet, it is only 2% of the total deaths of the Allied powers (Mougel, 2011). Turning to the perspective of the economy, if not cool-blooded, the exports of the States to Europe during wartime increased from 1.479 billion dollars in 1913 to $4.062 billion in 1917, and the increasing income tax had also brought a considerable amount of revenue to the government (Rockoff, n.d.). The war did not take place on the lands of the States, either. Henceforth, although the United States might share some of the fear that the Europeans were feeling after WWI, it was far less motivational than the European countries, nor did it induce a similar incentive for the States to bind itself with the European countries for the collective hope of the League, so as peace.

Inconsistency of fear shared among the members of an international order, furthermore, is a plausible attribution for the failure of sustaining it. In the case of the League, countries like France and Britain suffered significantly from casualties and losses from WWI, the fear was about the possibility of the vanishment of peace and the return of chaos. Germany and the defeated, however, were fearful of being continuously subordinated and controlled by the victories. As the fundamental ground of fear varied, their hope also deviated and became apparent in the 1930s. To Britain and other victories, the hope was to continue the peace at any cost. Consequently, they strived to negotiate with Germany and others even when the invasion had started. To Germany and the defeated, the hope was to reclaim their glory and status. As the states had inconsistent perceptions of fear, the priorities of states alienated, clashed, and led to the dismantlement of the order thereby. When fear is highly unified, in contrast, order survives. Mutual assured destruction is an appropriate example thereby. Anticipated that launching nuclear wars will cause massive destruction and human extinction, which will lead to a situation where the initiator could probably gain nothing, state parties are therefore extremely cautious and self-restrained of the employment of these weapons when conflicts occur.

Universal fears are crucial for the maintenance of today’s liberal order, therefore. Relevant attempts to keep the fears in line can be seen in at least three observable ways. First, as exemplified earlier in this section, the circulation of universal values (human rights, liberty, and democracy) is an effective method to establish an universal fear of being unable to embrace and practice those values. Second, international institutions such as laws, covenants, UN bodies, and international courts, which operate as regulatory tools for member states, legitimately and unavoidably impose fear on state parties. For example, member states have to submit periodic reports to the Human Rights Council by following the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) process. Reports submitted to UPR involve the human rights records of the state parties and are subject to suggestion or assail from other state parties. Flawed performance in human rights not only incurs reprimands but also possible detrimental consequences on, for example, the economy (because of sanctions), the image of the country (because of the news about its violation spread on media), and continuous pressure from states and civil society (because of the constant scrutinization or criticism posted by these parties)[3]. Similar consequences are anticipatable if it is about trade, hygiene, territory, or other issues that are subject to the jurisdiction of the UN bodies or agreements between state parties. The fear of encountering these costs, therefore, ideally motivates state parties to subject themselves to the established and formalized rules, which is presumed to be the most effective way to prevent additional losses.

Third, the enlarging membership basis of international and regional organizations and treaties enhances the enforcement of the two aforementioned methods and facilitates the universalization of fear. For example, ICCPR came into force in 1976 and has more than 170 state parties ratified in February 2023. The number has two implications. On the one hand, the large amount of state parties indicates that most countries and their citizens on earth became exposed to the hope and fear promoted by ICCPR in an official sense, that the states become responsible for securing political and civil freedom of their citizens. On the other hand, states who have not signed or ratified ICCPR undergo unceasing peer pressure. The fear of being excluded fostered the hope of recognition – which can be achieved when they decided to join the order. These efforts, intentionally and unintentionally, contributed to the sustainability of the contemporary order by establishing an universal fear among states and citizens.

To summarize, the hope for a peaceful, liberal, and democratic society requires the fear of chaotic, restrictive, and autocratic experiences. The liberal international order nowadays is an accumulation of past experiences of deaths and tragedies in human history. From them, it searches for hope – the hope of a sustainable future where human beings can live without those tragedies. ‘Order of fear’, which is thereby a reasonable categorization, in that if fear deviates, conflicts ignite; if fear entirely disperses or vanishes, the order collapses. Yet, emotion is a dynamic existence for which absolute unification is extremely difficult. When a deviation occurs and the fear it follows somehow transcends the fear of the order, agencies could behave in a rebellious and/or treacherous way toward the order. The behaviour of Russia and China in recent years are timely examples. On 24 February 2022, the Russian government decided to invade Ukraine by claiming that the military action is about disarmament and entazifizierung of Ukraine and is a counteraction to the threats imposed by Ukraine, NATO, and the allies, and to the bullies that they suffered for years (Putin, 2022, in Gardner, 2022). These threats precisely recall the memories of the Cold War and the invasion of Nazi Germany and motivate people to imagine what it would be if the Western power continues to suppress Russia and if Naziism burgeoned in Ukraine respectively. The fear exerted here outpaces the fear of war and death, nullifying the boundaries drawn by the international order. Comparably, the countless assertion of, for example, the evilness of the West, and the term ‘foreign intervention’ employed when the sovereignty of Taiwan is declared are other examples of the replacement of fear. The former recalls the Chinese with the memories of the history of the late Qing dynasty when China was carved up by foreign powers and defeated by the Eight-Nation Alliance in the late 19th to early 20th century. The latter escalates the emotional effects of history by pointing to an ongoing conflict with the West, which involves territory sovereignty. The fear of being inferior to the West replaces the fear of conflicts, which motivates citizens to support the government for its adoption of aggressive foreign policies in recent years.

Therefore, it is clear that when other fears prevail, the fear injected by the international order will be weakened, and the order becomes no longer sufficiently effective to constrain the behaviour of state parties. However, as the order has not yet broken into pieces, it also implies that the universal fear is yet not entirely dismissed. One plausible evidence to the statement, though controversial, is that states like Russia and China do not give up searching for justifications that are compatible with the rules and values of the international order, or at least in a ‘might right’ approach when they decided to take actions which deemed to be breaching the order. Noteworthily, if the priorities of emotion are malleable, the question becomes whether the fear presented by these countries is a natural consequence of uncertainty or human intervention (see section 4). Nevertheless, the reasoning and examples offered in this section argue that fear, instead of hope, has a primary role in the construction and sustainability of the contemporary international order. The universal fear [chaos and instability] the order presents bounds state parties together and envisions an universal hope [peace and stability]. When fear is unified, the order sustains and the behaviour is anticipatable; When fear varies, the order consequently shakes and the behaviour foundation for agencies deviates. An emerging number of states who behave outside the boundaries will be found thereof.

4. Rule by Fear

4.1. Calculus of fear and hope

Whereas fear cannot be completely obviated or dispersed if we would like to perceive hope, the artificial creation of fear deserves caution. To clarify the statement politically, it signifies that although the rule of fear underpins the contemporary liberal order of the international society and domestic order in a country, it should not be interpreted as unrestricted permissions for authorities to rule by fear. ‘What are the differences’, one may ask. Rule of fear refers to the fear which emerges as a natural consequence of the status of uncertainty; Rule by fear refers to the artificial manipulation of fear, which is an intentional creation[4]. Whereas both sorts of fear are motivations for individuals to do something, their nature is completely different. Imagine a situation that involves a social contract (or simply a set of common rules). In a state of nature, every person does not know when and how their assets, life included, will be plundered by other people someday in the future. The impossibility of predicting every decision of others, which is natural to human beings, induces great uncertainty in their lives. Consequently, they will be motivated to search for certainty regarding the benefits and losses. That is, to secure their benefits by relinquishing part of their rights (e.g. right to slaughter, to steal) and submitting to a credible common power (e.g. rules) in an equal way. By doing so, they receive promises of protection from unpredictable costs and become able to expect the behaviours of others and themselves. This is the case with the rule of fear, where the existence of fear and the pursuit of hope are both natural outcomes of the incapability of human beings to precisely predict the future. In the case of the rule by fear, the equation here involves human intervention. For example, to motivate person Y to submit him/herself to the rules, authority X incessantly sent burglars to cause harm to Y. When Y fails to put up with the loss and believes the perceived cost of joining the order is lesser than rejecting it, the order represents a saviour even when Y must renounce more than X to enjoy the protections.

Indeed, the employment of fear in politics has been well documented (e.g. Brader, 2020; Jost & Amodio, 2012; Kapust, 2008; Higgs, 2006; Prewitt, 2004; Steenbergen & Ellis, 2006; Stocchetti, 2007; Thrall & Cramer, 2009). The politics of fear not only matters for power relationships but also for the shape of a political community (Kapust, 2008, p. 2). It is such a powerful and cost-effective motivation tool to motivate or demotivate people to vote, to express, against, and/or, as argued in this article, to hope. Further developing on a sole portrayal of the political and psychological functions of fear, however, will be out of scope for this article. Pairing fear with hope, it will be interesting to investigate why fear but not hope is the most common form of emotional tool to be observed in politics. To simplify our understanding of the calculus of hope and fear, their relative relationship is visualized below.

Figure 1. Hope and fear of an imagination

Suggests that hope H and fear F are the endpoints of a line (HF) that rolls on the railways of X-Y-Z and AX-AY-AZ respectively. 10 is the longest distance between H and F and 0.1 is the smallest scale which the graph is set with. X and AX are the initial points where H and F can be felt off. This is the place where an imagination begins, starting with an uncertainty CT of = 0.2. CT is small because the possibility P is limited when an imagination is just a random thought in the mind. For example, person X daydreamed about new energy which is more cost-effective and environment-friendly that all existing energies on earth. The main fear which X could feel at this stage is forgetting the dream, consciously or unconsciously. Now, there are two ways to go. If X decided to develop the idea, HF will start moving rightward and the imagination grows and becomes more concrete. The imagination reaches the peak, where CT = 10, when X has finalized his formula for the energy and created a prototype of it. The future is so uncertain at this stage. Thinking negatively [fear], for example, his formula can be stolen by third parties, or the prototype malfunctions when it turns into a larger scale application, or he lacks resources to conduct further tests, productize it, and develop its market. In contrast [hope], he can also think of the revenue that he can obtain when he solely develops and productize the prototype, or the resources which he could secure for further experiments if he chose to cooperate with a well-established company, or the immediate gains when he decided to sell the formula to a company. Suggested that X decided to move forward by signing a contract with a company to productize the energy[5]. If everything goes well, HF should be moving closer to . X will reach with a CT = 0.2 when X only has one step remained before attaining the idea. For example, one second before the public announcement of the energy and the actual application of it. The uncertainty is small as albeit everything is possible in that second, the distance with attainment is so small that fear is nearly absent[6].

The explanation offered above briefly entails the relationship between the development of imagination, certainty, and the perception of hope and fear. Yet, not the reason why fear is the most commonly adopted emotion as a political tool for politicians and regimes. This has to be explained along with the graph shown below. Additionally, in order to simplify the explanation, the scale of figure 2 is changed to 1 instead of 0.1 which is suggested by Figure 1.

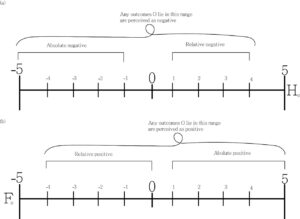

Figure 2. The scale of line HF

As suggested previously, the maximum distance between F and H (line HF) of an imagination is 10. Hence, the maximum fear is Fm = -5, whereas the maximum hope is Hm = 5. Any imagination should contain a F and a H which lies between 0 and -5 and 0 and 5 in a relative position respectively. Let’s assume that there is an artificially established H and F, namely He and Fe, which are located in the exact value of Hm (5) and Fm (-5) respectively. Imagine a situation where He is established at the first place and outcome O can be found. On the scale of -5 to 5, in a pure probability situation, less than He /11 = 9.09% of probability P that O = He. In other words, more than 90% of P that O will result in a smaller number than He. Although O is positive if O = 1~4, it is relatively negative when compared to He, and P is equal to 36.36%. Instead, the P of O= is near 50%, that any results lying there are perceived as absolute negative if it is compared to H(4~1) and He. The situation is completely reversed if Fe is the first established. The probability of a positive perception of an outcome is P = O(–4~4, exclude 0)/11 = 90.91%. Whereas O has approximately 50% of P to be absolute positive, it has 36.36% to be in relative positive when Fe is compared with. In addition, albeit 0 is a possible outcome, any O = 0 refers to a situation that either the imagination has been accomplished (> ) or extinguished (< ). Therefore, if the satisfactory of a person is highly associated with the outcome in an imagination, having Fe is clearly more likely to have positive outcomes than He.

Figure 3. The perception of outcomes in a situation with He or Fe.

4.2. The case of Hong Kong

The case of the democratization of Hong Kong in her post-1997 development can be used to further illustrate the calculation of He and Fe. In the last decade of British Hong Kong, Governor Christ Pattern announced a democratic political reform. Citizens in Hong Kong were allowed to elect their legislators, which they were only able to elect municipal officials in the decades before. While the imagination of a liberal and democratic Hong Kong was enlarging, the peak of imagination (Hm) was not found until the finalization of the Basic Law – the constitution of Hong Kong. In the constitution, for example, article 27 guarantees citizens their right to the freedom of expression[7], and articles 45 and 68 promise the citizens that, ultimately, the selection of Chief Executive (head of the government) and the congress will be done in universal suffrage. This is, undeniably, a clearly defined He[8].

Since He is found, every practical or foreseeable outcome which lies between -5 and 4 is perceived as negative and hence induces fear, grievances, and protests. This can be clearly observed from the democratic movement in the 2000s. In 2002-2003, the Hong Kong government sought to legislate Article 23 of the Basic Law, a law that prohibits activities that are against the national interests of China and the Chinese government[9]. Owing to its encompassing nature of prohibition and the history of the CCP, the legislation was criticized as fatal to the political and civil rights of citizens in Hong Kong as they believe the Chinese and Hong Kong government would exert their authority in an unlimited way like CCP did to her people in the past and the present (see Fu et al., 2005; Hung & Yip, 2012; Petersen, 2002). As the legislation has no merits to democratization but damages, this potential outcome is O(Legislation of Art. 23) ≤ 0, which is an absolute negative outcome. Henceforth, citizens were unsatisfied with the attempt of its legislation and protested the government intensively. More than 500 thousand of people participated in a protest and forced the government to step down. Eventually, the government decided to put the legislation on hold.

In 2014, as an example of relative negative, the Hong Kong and Chinese government decided to adopt a new political reform that contains universal suffrage for the head of government. On 31 August 2014, the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on Issues Relating to the Selection of the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region by Universal Suffrage and on the Method for Forming the Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in the Year 2016 was adopted by the Tenth Session of the Standing Committee of the Twelfth National People’s Congress (831 Decision). In the period of 1997-2014, the election of the head of the government was done by a committee that contained 1200 members. These members were responsible for nominating and electing candidates. For the legislative council, half of the council (35 seats) was elected by people in different sectors instead of universal suffrage. This half had often become the seats of the pro-China camp and curtailed the ability of the democrats to propose and pass private bills in the council. The 831 Decision, therefore, is one step forward to making the politics in Hong Kong more democratic, which is a relative negative that 0 < O(Political Reform under the 831 Decision) < He(Complete Democratization).

However, it was not satisfying enough for the citizens. The foremost reason is that the Decision limited the election of the head of government by confining the nomination process to a committee. That said, even if citizens could nominate their candidates, the government has the right to reject these candidates before letting them participate in the race. Consequently, some civil organizations and activists proposed a movement to force the Chinese government to revoke the 831 Decision and enable real democratic reform in Hong Kong. The Umbrella Movement outbroke in September 2014 as a result of it, where people went to the streets and practiced civil disobedience by occupying different districts (see Chan, 2015). Although the occupation was dismantled later in the year, the Chinese and Hong Kong government did postpone the decision.

Whereas hope is too wild to be harnessed, the Chinese and Hong Kong governments ultimately find that it is time to rewrite the emotion. On 30 June 2020, the Chinese government announced the Hong Kong National Security Law (Fe = -5) by bypassing the legislative council in Hong Kong. Different from the version in 2003 which was to legislate the law, the Chinese decided to utilize its authority to add the law into Basic Law by putting into Annex Three of the constitution. The governments neglected all objections and concerns and enacted the law immediately starting from the first of July 2020. The law is regarded as the murder of the freedom in Hong Kong, as it is designed to restrict citizen’s civil and political rights, oppress dissidents, and violate rule of law in Hong Kong (see Hui, 2020; Lo, 2021; Wong & Kellogg, 2021). For example, people were arrested and accused of violating NSL because of holding a white paper (Amnesty International, 2020). The law introduces an intense chilling effect in the society. Most representing pro-democratic politicians are arrested or in exile, organizations and media are forced to shut down or otherwise arrested by the police force, and citizens are living in a new reality where they need to face endless fear of oppression.

Now, the game was changed by the authority in a unilateral way. Although the articles promising democracy are not removed, the authority rewrote the configuration and successfully prioritizes fear in the perception of citizens. Instead of fighting for the hope (Complete Democratization), they are more subordinate to the fear (Total Loss of Liberty and Rule of Law under the National Security Law) nowadays. By utilizing the authority to create artificial fear, the governments find them much easier to control hope and explicit satisfaction[10]. For example, in October 2022, a citizen applied for a judicial review against the decision of government to invalidate the certificates waiving the COVID-19 Vaccination Medical Exemption Certificate (VacCert). The VacCert is a document to authenticate one’s vaccination history. During the pandemic, the Hong Kong government required all citizens to obtain the VacCert or other they cannot enter shopping malls, attend schools, or go to work. In order to be waived vaccination, some citizens went to hospitals or clinics to ask the doctors to issue certificates for waiving the VacCert. Yet, the government found that some certificates were obtained without medical reasons and decided to invalidate all of them regardless of the reasons. As a result of the review, the decision of the government was overthrown by the court and the plaintiff told the media that the success of review is a fact to imply that rule of law still exists in Hong Kong[11]. Indeed, the outcome is relatively positive in that O(Successful Review) > Fe(Total Loss of Liberty and Rule of Law under the National Security Law) = -5. Yet, if this outcome is attained before the National Security Law, it would be no more than an ordinary outcome as rule of law was better preserved in that era. In short, it means that the same outcome will be perceived differently when the prevailing emotion is changed. By modifying established hope into fear, even the most common outcome in a society of hope and be a hope in a society of fear. That said, a rule by fear can enlarge the fault tolerance and the possibility of satisfaction of citizens toward the ruling authorities.

The case of Hong Kong in these 20 years shows the difficulties for authorities to govern when He prevails. In the situation of He, a small loss or failure to attain He will be perceived as an unsatisfying result; while in the situation of Fe, a tiny gain is perceived as better than nothing. It also reflects the fact that when the power of the government is not limited, the game can be changed easily by ignoring the will of its people. Some may argue that the control of emotion is not complete in that O > Fe does not mean people are satisfied. They could be unsatisfying toom, but they are not able to express their feelings only. The statement is true per se, but it ignores a fact – the history of the people. To the current generation who has (had) fought for democracy and freedom in Hong Kong in the 1990s-2020s, they have been through a transition from He(Complete Democratization) to Fe(Total Loss of Liberty and Rule of Law under the National Security Law). Their dissatisfaction with Fe originate from its comparison with He(Complete Democratization) and because the people know Fe is an artificial creation of the CCP in China. 40 years later when the pro-democratic citizens left Hong Kong and/or passed away, the new generations are born in the era of fear and educated to stay with the fear. The effect of He(Complete Democratization) will hence lose its influence and the Fe(Total Loss of Liberty and Rule of Law under the National Security Law) will no longer be merely a fear. To these new generations, the society without adequate political and civil rights is the normal society that they are living in as they have no taste of the liberty which citizens enjoyed in the 2000s-2020. This is not an artificial product, but an ordinary form of society[12]. There are no internal comparisons, nor would they regard the democratization of Hong Kong, if this idea still exists, the same He as the previous generations. As long as the authority of the CCP remains stable, the artificial fear that it imposed on Hong Kong can be extremely long-lasting. Combined with education reforms, the authority could turn the de facto artificial fear into a natural reality to the new citizens. Starting from that point, every single outcome which lies slightly better than the new reality would be regarded as satisfying and/or even as hope. And this is the exact danger that artificial fear carries.

4.3. Artificial fear

Once fear is manipulated, hope follows. The employment of fear empowers the ruling parties to control the scale of satisfaction and hope of future generations, especially when the fear is not about the regime itself but of external parties. For example, the fear of being oppressed by the West (adopted by the Russian and Chinese governments), the fear of being invaded by China (adopted by the Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan), and the fear of terrorism adopted by the United States after the 911 incident). Although political fear is found in democratic countries too (as mentioned previously), the utilization of fear is more frequent and critical in authoritarian ones. From imprisonment (e.g. the continuous arrestment of rights protection lawyers in China) to death (e.g. a girl was dead after being arrested in Iran in 2022), fear is such a powerful weapon for these authorities to exert their power[13].

As argued in the previous sections, the stability and sustainability of the liberal international order are closely associated with the degree of unification of fear. Artificial fear, whether admit or not, can also be found in the order. For example, the penalties stipulated by the laws and conventions enforced by international organizations (U.N. in particular) are crucial conditions to make the agreements effective and credentialed. Without replicating the arguments in sections 3 and 4, these penalties are the fear which encourages individuals and state parties to remain within the behavioural boundaries which are commonly shared in the same society. Without visible coercive forces, the behavior of others becomes unexpectable and uncertainty increases. Moreover, though arguable, the reaccentuation of the tragedies which humans experienced in the past and the promotion of human rights are also examples of artificial fear. The former is consistently inputting a particular set of information to all generations and shaping the behaviour in a specific way through the fear of repeating the history (e.g. war and genocide); the latter is circulating the fear of not being able to attain the human rights which they are told to enjoy.

Yet, the fear imposed by the order can be challenged by another fear which is established by the state parties. One of the greatest weaknesses of the artificial fear of the order is that it does not have adequate coercion or influence to bypass the states and reach the people directly. The key determinant of whether the content and emotion of the order can reach the people or not is the state parties. If the states refuse to let their citizens acquire the information which the order would like them to receive, the order does not have many choices but to hope the people themselves can find a way to receive the information. In sharp contrast, a state has the ultimate power to decide what emotion and information the citizens of its should share. Through controlling education, public speeches, and the accessibility of information, the citizens of a country can be shaped to uphold a relatively different set of fear and hope than the order promotes. For example, although the order emphasizes multilateralism, peace, and tolerance, the U.S. was driven into a fear of terrorism after the 911 incident which the emotion directed the citizens to support the counter-terrorism military actions which were launched by the U.S. government in a unilateral way. Whereas the civil society in a democratic country can be intelligent enough to hinder the attempt of the ruling party from imposing an artificial fear (because of their power to elect officials and rights to freedom, including the rights to information and expression), the situation worsens if the regime is a dictatorship or authoritarian (e.g. North Korea, China, and Russia). Civil societies in these countries are highly confined and the authorities have utilized miscellaneous methods to shape the emotion of their citizens. Typical methods include extreme patriotic and nationalistic education, information control through censorship, and inciting speeches (probably involving the glory of the country) from politicians. In short, states utilize the gap between the international order and domestic society and introduce a different set of fear to their citizens. The state-founded fear is inconsistent with the fear promoted by the order, and therefore hampers the unification of emotion and gives rise to conflicts.

To slightly further the discussion, it must be realized that the artificial fear itself is not the problem to the order (as it contributes to the construction of the order), but the excessive usage of it is. Echoing Kapust (2008, p.13), it is necessary to limit the authority from accessing the power of establishing and employing fear. Otherwise, the international order will never be stabilized as every single state will have the capability to carry its people to a different proposition from the places which the order suggests. There are two ways to constrain the states. First, it is a domestic method that emphasizes the role of civil society. The civil society of a country should be cautious of any attempts which the ruling party took to create fear artificially. The creation can take place in the legislation process of a new bill, or a speech was given by the head of the government. Civil society should deliberately reflect on the information they received and be fairly active and critical of the decision of the authorities. Once they found an excessive usage of fear (e.g. prohibiting all political speeches for the sake of state interests), they should pressure the government to relinquish such attempts. Second, it is an international method that suggests the states strengthen mutual supervision and enable international organizations to take regulatory action more seriously. In principle, any artificial fear should also be put into a position to, and merely for this purpose, serve the hope of the liberal international order. Such fear must be kept thereof. However, if the fear is imposed to serve the interests of a small group of people, and/or if the rules and penalties it introduces are vague and easy for manipulation, and/or if the subjects are excluded from the (re)construction of it, then the fear employed in this case should be prohibited. Therefore, if the liberal order needs to be stabilized, the cardinal condition is to prevent any attempts which state parties took to diverge their citizens from the international society for the pursuit of national interests. Yet, the question is: to what extent and how could this be achieved? This will be discussed in the next section.

5. The Imagination of Future

As argued previously, an universal fear can unite the expectation (hope) of state parties and individuals and hence shapes their behaviour. It is the cornerstone for which an order can be preserved between parties who have different cultural and geographical backgrounds. To sustain a peaceful international order and humane relationship, therefore, the most effective way is to establish a common set of fear. Environmental issues, for example, are one attempt to formalize the universal fear. However, it seems that it is too weak, or simply non-imagination-inducing enough to alert parties to prioritize its dangers of it. The nuclear threat is the closest form of effective fear in that every party is exposed to a fear of extinction. Yet, it has two weaknesses. First, not all states have nuclear weapons. It implies an imbalanced relationship in which some parties can only be a receiver of the threat but not a constructivist of it. Second, the fear of our extinction can be overwritten. In an interstate war where A against B and B is losing it. The “our” mentioned earlier becomes the people of B, but not A. If they can preserve “our” existence by erasing “their”, B would not be hesitant to do so – even if the chance is merely 1% higher than not doing so – and vice versa.

The interpretation of fear and our continues to diversify in foreseeable future, unfortunately. It is foreseeable that the Russian invasion of Ukraine continues in 2024 and beyond. The war is prolonged by the armament supplies provided by NATO and China (and North Korea) to Ukraine and Russia respectively. Despite the enormous number of casualties, both blocs insist on their own just and fear and believe that the war must go on until one surrenders. The weapon suppliers, too, have their fear. Within the Western bloc, the United States is fear of the consequences of authoritarian expansion and the threats which it will impose on the power status of the States, whereas Germany and France are fear of the return of European warfare led by the vengeance of Russia when it encounters total defeat. As a sort of shared fear, they both fear the collapse of the contemporary international order – an order which emphasizes liberty, rules, democracy, and multilateral relationship. China, in contrast, is fear of being the sole player against the West and its values if Russia lost. Albeit the sources of fear are diversified, the facts of fear motivate them to support either side of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Yet, it is also foreseeable that the intensity of conflicts between Russia and Ukraine will start reducing in the following years. It is not because of formal cease-fire treaties or if a party has obtained a total victory, but mainly the exhaustiveness of their people and armies. On the side of Asia, China continues its aggressive diplomacy and repressive domestic governance. It shows no intention to balance freedom and control in Hong Kong, nor to give freedom to Tibet and Xinjiang. the government continues to colonize these territories by sending thousands and thousands of Chinese to dilute local influences and reduce their possibilities of successful rebellion. President Xi is fear of relinquishing his power, and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is fear of losing its leadership in the country. The utilization of the fear of an aggressive West continues to contribute to the hope of a great China. The aggressiveness of China inevitably concerns its neighbouring countries and Taiwan comes first. Since Hong Kong falls in the fight for freedom, Taiwan has become the last piece to complete President X’s great puzzle of an integral China. Xi and the CCP further their propaganda of duty to reconquest Taiwan and intensify their political, economic, and cultural intervention. Such behaviour increases the level of uncertainty regarding regional peace and aggravates the fear of Japan, Korea, and the Philippines, which are the three countries that are aligned with the United States and have deployed military bases there. Once the invasion is signified, these countries have no choice but to be involved in the defence of Taiwan and/or their land[14].

In the worst situation, the war in Asia would not be the first nor the last. Since Russia was de facto defeated[15] in the Russian-Ukrainian war, the emotions of fear and anger never ease even when the scale of conflict has been shrinking since 2024. The costs which Russia paid for the war have pushed the country to the edge of dismantlement. The fear of “a Russia without power” and/or “Russia in pieces” grounds the country for a war of vengeance, for which the most suitable opportunity is the declaration of China on invading Taiwan. Since the major powers are engaged in war, some countries are finally free from the strings imposed previously. Israel, Serbia, Afghanistan, and other countries that have intermittent military conflicts with adjacent countries will continue their warfare in an explicit way. Ultimately, East Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East will become the three major war zones in the 2030s.

Since Moisi’s work was published around a century ago – and the hope that he imagined did not come true – this article would also like to follow his steps and offer two imaginations of hope from the fear of a world congest with variants of fear: An idealistic future where fear is universally unified and sustained, and a realistic future where artificial fear is fairly maintained and confined.

5.1. Idealistic Imagination

Began from the Chinese invasion in Taiwan and Russian invasion in Eastern Europe, unprecedented damages are brought by the new world war which the two previous world wars are completely incomparable. Several governments collapsed during and after the war. The tremendous number of casualties, nuclear pollutions, and other damages the war caused push the human society to the edge of extinction. The fear of extinction awakes state parties and individuals and motivates them to realize the deadliness of the peruse of distinct interpretation of emotion and interests. Eventually, an unprecedented hope was born from this unprecedented fear in human society – the establishment of a global government. The common fear, now, is unified and prioritized, and semi-perpetual perhaps, becomes the grounds for a single deterrent force. Sole claims on state and national interests no longer exist. Instead, the government focuses on the balance of interests of all mankind. The government is operated in a manner that endorses rule of law, liberty, tolerance, plurality, and communication. It focuses on promoting the equality between different ethnics and tries its very best to make the society inclusive to them. The elimination of discrimination and nationalism will be the priorities of work which the new global government should work on.

Another factor, rather than a deadly warfare, can also lead to the aforementioned outcome – a shared enemy of all mankind. Scapegoat mechanism is frequently used by politicians and states to redirect sentiments toward a greater enemy. The motivation for domestic unification is nearly unstoppable when there are perceivable external threats. Whereas threats like environmental problems are too weak in strengthens, one possibility is, if not too imaginary, threats outside the earth. For example, resources have been suggested as a critical problem to human society in the future. Although states and companies continue their efforts to invent new energy, land, or food resources, it is very unlikely that the problems can be settled. As a result, states begin exploring the universe and to build viable environment for mankind to live in space. Yet, someday in the future, a threat comes from the space, such as an unknown specie from other planets or the fall of the meteor. Regardless of the details, such threat must be external to earth and fatal enough too all living beings on earth. When the scapegoat mechanism expands to the scale of entire human beings, it becomes possible to unify fear and hence hope. Consequently they will be encouraged to respond to the threat as one but not fragmented many. Yet, noteworthily, it is doubtful if the world government and peace formed by the mechanism could be as perpetual as those formed from brutal history. Since the effect of the mechanism decreases when the threat is resolved, the unification of emotion can be provisional. Rather, the brutal history will not disappear, and can be consistently reminded across generations through education. Nevertheless, both imaginations are only in an ideal situation.

5.2. Realistic Imagination

An universally prioritized and shared fear will never exist. It is inevitable for human society to uphold different perceptions of fear and, sequentially, hope. As variant fears prevail, conflicts between states never cease. However, the rules and other coercive forces found for the current order did not vanish. Although wars (mainly the Russian-Ukrainian and Chinese-Taiwanese warfare as predicted) continue, they did not escalate to a situation where the international order fully collapses. They maintain a minimum behaviour to the order and search for a sustainable justification for their acts within the framework. National fear and interests are the priorities, yet, the United States, Russia, China, and other major powers also fear losing their influential status in the order. That said, they are behaving in a more unilateral way in the name of multilateralism.

With continuous military conflicts, however, the international order is moving forward positively in two incremental ways. First, the concept and education of global citizenship continue to develop and expand in school education. This will be mainly started in the Western and Northern European countries, where liberal and peaceful values are better enshrined. Most importantly, the European Union is a great carrier to educate global citizenship with practices and experiences. Pluralistic countries are more likely to further develop this type of citizenship too, such as Canada. For the U.S., the attempts to further the consciousness of global citizenship among citizens are not directed by the government, but the civil society. The sides of Russia and China are quite different, though. The promotion of global citizenship in these countries, secondly, requires the citizens there to awaken from extreme patriotism and nationalism, which are instilled by the governments, and to pressure for changes. Both countries need to be more pluralistic and exposed to greater interests than the national ones. Yet, the challenging fact is that the governing leaderships in these countries are not that like the U.S. or Western Europe where power is in the hand of the people. It seems less likely that they will spontaneously forgo their power in the country. Hence, the role of citizens in Russia and China is far more important than those countries which are already liberal and democratic. Changing from passiveness to activeness, nationalistic to globalistic, and obedient to evil to strive for goods are crucial factors to reform the states in a more rule-based manner. When rule of law is highly restored, citizens will be free from the arbitrary power of the governing parties. Since the absolute power of states is curtailed, civil society becomes more capable of supervising the government and initiating multifaceted changes. The priority should hence be given to the construction of a country where citizens are receptive and tolerant to diversity and can express themselves freely in communication. This is where and when global citizenship should be promoted. The situation is slightly similar in the Middle East. Society must first realize and counter the artificial fears created by their government and their values, namely the worldview of exclusiveness. They must not be fear of the consequences of inclusiveness but of exclusiveness. They should search for commonalities and cooperate for a future where involved parties are mutually satisfied.

In 2030, global citizenship education prevails and nationalistic citizenship education declines. In 2045, students who undertook global citizenship education became adults in society. The knowledge, skill, and attitude instilled in schools continue to develop and become the behavioural cues to their decision-making mechanisms. They practice globalistic values and help further the influences of education across societies. Now, for example, the U.S. is less talking about unilateral actions and the fear of losing power, but about cooperation; Russia is less talking about the distinctiveness of Russia and the fear of the west, but about common values; China is less talking about a great China and the fear of liberalizing the country, but about tolerance. Yes, there are different interests; Yes, there are different cultures; and yes, there are different fears. However, society in 2050 are more accommodated and calibrated to bargaining and negotiation in the political sphere. And to accomplish this imagination, it needs a rule-based society where the power of authorities is restricted, where people can practice tolerance by expressing their own thoughts freely, and a trigger to establish a relatively universal hope from a relatively universal fear. The expansion of the Russian-Ukrainian war and the anticipated outbreak of the Chinese-Taiwanese war are treasured triggers to activate the imagination. The activation and execution of it, therefore, should not be solely dependent on the state parties, but also on the people who are a member of them.

6. Conclusion

Can we live with hope but not fear? Unfortunately, this article denies such thought. It echoes with philosophers like Spinoza, Post, and Descartes and upholds that hope and fear can only be felt when both exist. Either side missing will cause a failure of the imagination of the other. If there is peace, we need not imagine peace; if we have love, we need not imagine love; if we have achieved all we want, we need not imagine. Our imaginations exist only when the imaginations are not yet achieved when the world is not closed. This is exactly the foundation of human society and the contemporary liberal international order. The order is a hope that suggests a future that equality, diversity, and peace prevail. Yet, the very existence of this imagination is unshakeable evidence of the failure of humans to attain them in the past and present. It is precisely the tragedies, wars, and deaths, that human beings have been through, that direct the contemporary world to a path toward the hope that the order promotes. As the foundation of the order is strongly associated with the emotion of fear, a commonly shared fear, this article does not agree with the claims or imaginations of a future with ‘more hope and lesser fear’ in that both emotions either enlarge or shrink at the same time. If we ask for more hope, we must acknowledge that we are simultaneously asking for more fear. That said, hope should not be the sole emotion that we should look up to, nor should fear be the sole emotion that we should be afraid of. This article argues that fear must be recognized, admitted, and faced if one would like the hope to continue to exist and expand, and a high degree of unification of fear is the only way to reduce interstate conflicts. Since hope is a consequence that emerged from fear, this article further argues that unifying fear will help articulate the state parties to point in the same direction. Otherwise, diversified fear will incur conflicts and encourage states to pursue their interests. Therefore, instead of merely fear, the excessive usage of artificial fear for the pursuit of private interests is the true cautious point of which state parties and civil societies should be aware.

This article also proposes a formula that visualizes the relationship between hope and fear. It theorizes why fear is more likely to be employed than hope in politics and how fear can be manipulated to determine hope. Yet, this article does not delve into how the manipulation connects with the actions (e.g. voting or protest) of agencies in that it is out of the scope of this article. Since conventional calculations of these political actions are grounded on rationality and are mainly focused on the relationship between the probability of outcomes, cost, and duty, perhaps it needs a renovation to include emotion as well in that rationality and emotion are not mutually exclusive but are both innate components for human beings to live on. One possible calculation is: . Whereas A and S refer to Action or Silence respectively, C means the Cost to resist Fe or He and D means the sense of civic duty. If the result of the equation is negative, then the agent should remain in silence (S); if it is positive, then an agent should decide to act (A). Nevertheless, it will be the duty of another article to substantiate the formula and to study how external manipulation of emotion can be potent in decision-making processes, whether it is about voting, protesting, or rebel. Future studies should also pay attention to the relationship between the artificial creation of fear that state parties adopted and the level of conflicts occurring/ed between them. It could further clarify the role of fear in terms of how it can contribute to peace and conflicts in the international society, and hence search for suitable ways to sustain or enhance the international order in the future.